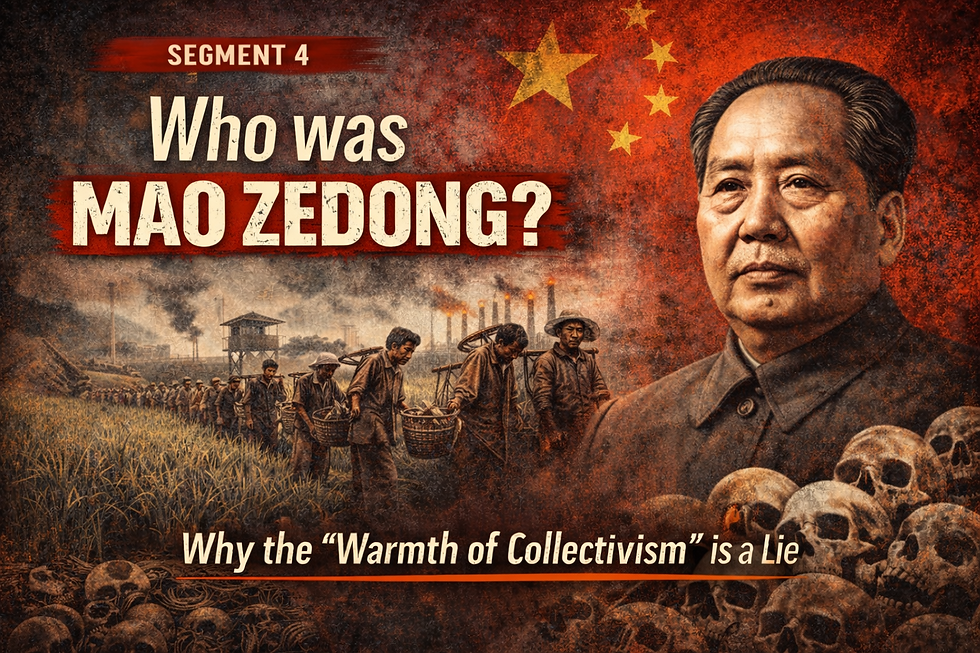

Why the “warmth of collectivism” is a lie, Segment 4: Who was Mao Zedong?

- dktippit3

- 1 day ago

- 5 min read

If Pol Pot is the shock of collectivism in miniature, Mao is collectivism at scale, not just a revolution, but a national experiment. And it’s one of the clearest historical examples of what happens when leaders try to vote reality off the island with ideology.

Mao Zedong was the founding leader of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and, for decades, the defining figure of Chinese communism. Britannica describes him as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the 20th century, and it notes that several of his signature campaigns had “disastrous consequences” for China’s people and economy.

That’s the entry point for this segment: Mao wasn’t a footnote. He was a governing philosophy with the authority to enforce it.

Mao’s “warmth” wasn’t primarily economic — it was moral and total

The pitch wasn’t merely “we’re going to share.” It was closer to: we’re going to remake the human person. A new society requires new people. And new people require new loyalties.

That’s why Mao’s major projects weren’t just policies, they were mass movements that demanded participation, conformity, and emotional buy-in. The goal wasn’t “help where needed.” The goal was transformation: culture, economy, family structures, education, faith, and even memory.

You can call that “progress” if you want. But historically, it functions like a substitute religion: a salvation story with a political Messiah.

The Great Leap Forward: when slogans replace crops

The Great Leap Forward (1958–60) is where the poetic promise turns into a measurable catastrophe.

Mao’s plan pushed rapid collectivization and industrialization, famously including “backyard furnaces” meant to boost steel production, while reorganizing rural life into communes. The problem is simple: you can’t organize a nation on motivational slogans. Crops don’t grow better because the government feels hopeful.

Britannica’s summary of the consequences is stark: the Great Leap Forward led to a massive decline in food production and a famine in which about 20 million people died of starvation between 1959 and 1962.

Other credible estimates go much higher. Britannica’s “Facts” page notes “recent estimates” as high as 45 million deaths. And the Association for Asian Studies (teaching resource) summarizes scholarship that ranges from 23 million to 55 million, with 30 million often cited.

You don’t have to pick the highest number to make the point. Even the conservative mainstream estimate is horrific. The bigger point is this: when the state controls food, error becomes fatal, and leaders who can’t admit error tend to punish whoever exposes it.

Because in centrally planned systems, bad news is not merely inconvenient. Bad news is disloyal.

How it happens: “warmth” becomes compulsion, then punishment

This is the part that keeps repeating across regimes, but Mao gives it unique shape:

Centralized planning creates goals that reality can’t meet.

Local officials lie to avoid punishment—over-reporting output, hiding shortages.

The center makes decisions based on false data.

Procurement quotas keep extracting food anyway.

Starvation spreads.

Anyone who says, “This isn’t working,” becomes a threat to the narrative.

The tragedy here isn’t only famine. It’s the way ideology corrupts truth. Once a leader builds a system where people are rewarded for saying what the center wants to hear, society becomes one giant echo chamber—and real people pay for the hallucination.

This is where “toxic empathy” enters.

Because Mao-era rhetoric often framed suffering as proof of virtue: sacrifice for the collective mission. If you resisted, you were selfish. If you questioned, you were reactionary. If you complained, you lacked revolutionary compassion. The emotional appeal—do this for the people—became the moral cover for coercion.

And that’s the real trap: compassion language can be used to criminalize honest reality-testing.

The Cultural Revolution: when the revolution turns inward

If the Great Leap Forward shows what happens when collectivism tries to control nature and economics, the Cultural Revolution shows what happens when collectivism tries to control culture and conscience.

Britannica describes the Cultural Revolution as beginning in 1966 and ending after Mao’s death in 1976, and notes that it left many people dead, displaced millions, and disrupted the economy; it reports death estimates ranging from 500,000 to 2,000,000. Another UK educational resource gives a similar range: 500,000 to 2 million. Stanford sociologist Andrew Walder has published newer calculations estimating 1.6 million deaths.

What’s most revealing about the Cultural Revolution isn’t just the number. It’s the method.

Mao mobilized youth, Red Guards, and encouraged a campaign against the “Four Olds” (old ideas, old culture, old customs, old habits), which often meant public humiliation, “struggle sessions,” violence, and the destruction of cultural and religious sites.

Here’s the thread: a collectivist movement can’t tolerate rival authorities; family loyalties, religious commitments, inherited traditions, because those loyalties compete with the collective mission. So the mission turns those things into enemies. Not “different.” Not “private.” Enemies.

And once your moral imagination is trained to believe that enemies deserve whatever happens to them, cruelty becomes a form of righteousness.

“Reform through labor”: making captivity productive

Another Mao-era feature worth naming is the development of laogai (“reform through labor”), a penal labor system tied to political control and “re-education.” A U.S. congressional hearing record describes laogai as a “vast labor reform system” used as an instrument for detaining political dissidents and penal criminals, with forced labor as a core function.

You can think of it as the bureaucratic version of the same logic: if the mission is ultimate, people become material, something to re-form, re-educate, re-purpose.

Again: not warmth. Not care. Control.

What Mao teaches us that Stalin and Pol Pot don’t—quite as clearly

Mao is especially important because he shows how collectivism doesn’t just seize resources. It seizes reality.

In the famine, reality is rewritten through false production reports.

In the Cultural Revolution, reality is rewritten through coerced confessions, public denunciations, and social terror.

Through re-education systems, reality is rewritten by forcing people to speak the approved words until the approved words become survival.

This is why “warmth” is such a persuasive marketing term. It makes the mission sound humane. It makes objections sound cold. It pressures ordinary people to stop asking hard questions, because hard questions feel unkind.

And that’s the point you’re building through the series:

Warmth that requires compulsion isn’t warmth. It’s a furnace.

Where we go next

Mao’s story sets up the next segment perfectly, because it raises the question people always ask after seeing disaster:

“Okay, but that wasn’t real socialism, right?”

Next segment: Hitler—because collectivism isn’t only economic, and total control can be pursued through race and nation as easily as through class.

.png)

Comments